Professor Austin Tate, Director of the Artificial

Intelligence Applications Institute (AIAI) at the University of Edinburgh,

discusses progress made in AI and what could be in store...

Professor Austin Tate

The field of artificial

intelligence (AI) has been characterised by some very optimistic projections,

coupled with an underestimation of the time and effort needed to produce

intelligence in machines. The impression many have of AI is gleaned from science

fiction where it may be portrayed in a human-like robot such as David in

Spielberg’s ‘A.I. Artificial Intelligence’, the crazed HAL in Kubrick’s ‘2001: A

Space Odyssey’, or super human (and often malevolent) entities such as Skynet in

Cameron’s ‘Terminator’ movies. Given such a fantasy portrayal it is not

surprising that reality may seem a little out of step with expectations.

I am an optimist and believe that AI methods (in particular

knowledge-based systems) will allow us to make much better use of information in

support of the tasks we wish to carry out, such that the processes involved will

be more transparent, open and explainable.

Professor Austin

Tate

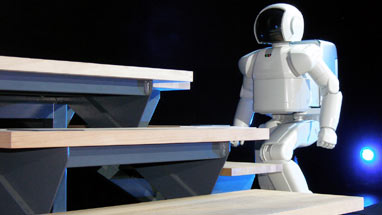

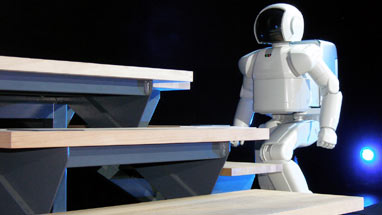

Physical and reasoning aspects of robots both require much work.

Interacting with the world in a useful way is a big challenge. Though we are a

still a long way from realistic biped bodies with humanistic movement, great

strides have been made in this direction at a number of labs in the last decade.

A car has driven across the US ‘hands-free’ using sophisticated AI visual

processing and vehicle control software and the state of Nevada has now licensed

autonomous cars. In some US Grand Challenges, autonomous vehicles have driven at

high speed over rough terrain. Biped robot exoskeletons with AI adaptive systems

technology are becoming available and have assisted disabled people in walking

again.

The intelligence in an AI is normally in the software that runs on

a computer. There are many very clever, knowledgeable or intelligent programs

working on well-defined problem domains and helping people in their everyday

lives without them even being aware of it. However, brute force systems like the

core of IBM’s Deep Blue (the chess playing program/computer) do not strike me as

very intelligent. Rather, they are powerful and able to search many

possibilities in a short space of time. I would describe as more intelligent the

software on board the Deep Space 1 spacecraft that employed autonomous

intelligent planning and control software as it performed its mission.

In

terms of the synergy between increasingly capable computer systems and AI, AI

has influenced general programming language design from the very earliest days

of computers (eg, via LISP in the 1950s), and continues to do so, for example in

the design of Java. AI has always been a computation intensive activity, and

some techniques have come into their own as computing power has

grown.

This applies very directly to tasks such as speech understanding,

visual processing, and other aspects of robotics. Improvements in raw computing

power also facilitate headline catching AI such as IBM’s Watson computer having

enough knowledge and information to win over previous champions in the

‘Jeopardy!’ TV quiz in the USA.

Game playing was an early focus for some

AI researchers for decades. The attempt to get computers to play chess allowed

us to begin to understand the different mechanisms involved in intelligent

reasoning and planning, a problem that is considered ‘solved’ since Deep Blue

won a series of games at grand master level. Perhaps a more interesting example

is that AI planning technology is embedded in a low-cost consumer device to play

bridge – the ‘Bridge Baron’.

There are some general purpose AI methods

that are frequently used or embedded in many deployed systems. These include

heuristic search, constraint solving, rule-based reasoning, and adaptive

techniques such as genetic algorithms. Areas of application

include:

• Finance (insurance underwriting, fraud detection);

• Supply

chain management;

• Crew and equipment planning and scheduling;

• Advanced

manufacturing and assembly;

• Oil exploration;

• Many uses in aerospace,

defence and telecommunications.

In the USA, the Defense Advanced Research

Projects Agency (DARPA or ARPA) has provided a stimulus to the advancement of AI

techniques in many fields over the years. They were instrumental in setting up

competitions that drove natural language and speech processing systems, such

that they are capable enough for use in many online assistance and personal

mobile devices. In one DARPA initiative in the 1990s to develop AI planning and

scheduling technology, an early focus created a system to improve the scheduling

involved in moving materials for military missions. A U.S. Department of

Commerce report in 1994 stated that the deployment of this single logistics

support aid during Operation Desert Shield paid back all US government

investment in AI and knowledge-based systems research over a 30 year

period.

We are still a long way from realistic biped bodies with

humanistic movement, but Honda's Asimo demonstrates how far we have

come.

In my own field of AI planning and collaboration, an example of

a deployed application of our results is in the flexible re-planning of the

assembly, integration and testing of the payload bay of Ariane rockets for the

European Space Agency. This sort of application of AI can be found in many

engineering sectors.

When you pick up a copy of the Yellow Pages in the

UK, its layout has been done using AI constraint-based layout methods developed

jointly by industry and my research institute that allows for immediate feedback

on placement of adverts to generate increased sales opportunities with potential

advertisers, improves the layout to keep customer information close to adverts,

and uses significantly less paper resources in the final products.

The

growth of the web has been a recent driver for work on semantic representations

and using reasoning facilities to create the so-called ‘Semantic Web’. Data

mining and extraction or classification of large datasets from science and

engineering in fields such as drug discovery and particle physics, as well as

from commercial operations such as advertising and banking, have been very

productively used to scan and classify vast quantities of data, eg from

astronomical observations.

The successes of AI to date (and only some are

widely recognised) have formed a solid basis for realistic exploitation and

excellent prospects for future development. The ‘knowledge bottleneck’ that

needed to be addressed to make intelligent systems a reality is being solved

through the growth of the web, online social networking, and knowledge sharing

for professional uses.

I am an optimist and believe that AI methods (in

particular knowledge-based systems) will allow us to make much better use of

information in support of the tasks we wish to carry out, such that the

processes involved will be more transparent, open and explainable. This will

profoundly affect the ways in which verification of compliance with standards,

legislation, safety rules and so on will be possible for individuals,

organisations and governments.

It is in the nature of any technology that

it can be used for good or for bad. If AI systems are seen as agents of their

creators or the groups that deploy them, then accountability must reside with

those that put such systems into use. That is a general concern we all should

have whether we are talking about tools such as a hammer, a car, a computer

controlled train or elevator, an automated financial stock dealing system or an

unmanned autonomous vehicle.

In future I believe we will see deep space

probes and rovers with advanced automation and AI travel out from our planet

sending back home exciting discoveries. Autonomous sea, land and airborne

vehicles will explore parts of our own planet too inhospitable for people to

travel there. Humans and robots will work alongside one another in emergency and

rescue situations, and protect building occupants. We will be able to have a

personal assistant or co-worker who will work alongside us, get to know our

tasks, processes and preferences. It will do those things you wish you had time

to do yourself but that are never at the top of your agenda. The same systems

will adapt themselves to become an active aid as you and your family age.